The looms in India have been at work for over 5,000 years. The imagery of the loom is woven into our poetry – from the Vedas to our folk ballads. So powerful is the spinning wheel, that the charkha became one of the symbols of the struggle for India’s independence. The forms of the loom kept changing but handwoven cloth was and is an intrinsic part of the warp and weft of India’s intangible cultural heritage.

Join Cultural Samvaad’s WhatsApp community

A Few Words on the Historical Legacy of Indian Handloom

Cotton, wool and silk cloth were all present and in use during the days of the Indus Valley Civilisation or Harappan Civilisation (Jonathon Mark Kenoyer). Even while archaeologists and historians continue to unravel the mysteries of the Indo-Saraswati basin, it is probably not wrong to aver that for most of recorded history, India has been a pre-eminent producer of textiles. Writing in the 1950s, John Irwin commented on the legacy of the handloom traditions in The Museum of Modern Art catalogue. “As early as 200 B.C., the Romans used a Sanskrit word for cotton (Latin carbasina, from Sanskrit karpasa). In Nero’s reign, delicately translucent Indian muslins were fashionable in Rome under such names as nebula and vend textiles (woven winds), the latter exactly translating the technical name of a special type of muslin woven in Bengal up to the modern period. The Periplus Maris Erythraei, a well-known Roman document of Indo-European commerce, gives to the main areas of textile manufacture in India the same locations as we would find in a nineteenth-century gazetteer and attributes to each the same articles of specialisation. The quality of Indian dyeing, too, was proverbial in the Roman world, as we know from a reference in St Jeromes fourth-century Latin translation of the Bible, Job being made to say that wisdom is even more enduring than the dyed colours of India. The influence of Indian textiles in the English-speaking world is revealed in such names as sash, shawl, pajama, gingham, dimity, dungaree, bandanna, chintz, khaki – these are only a few among the textile terms which India has exported with her fabrics.”

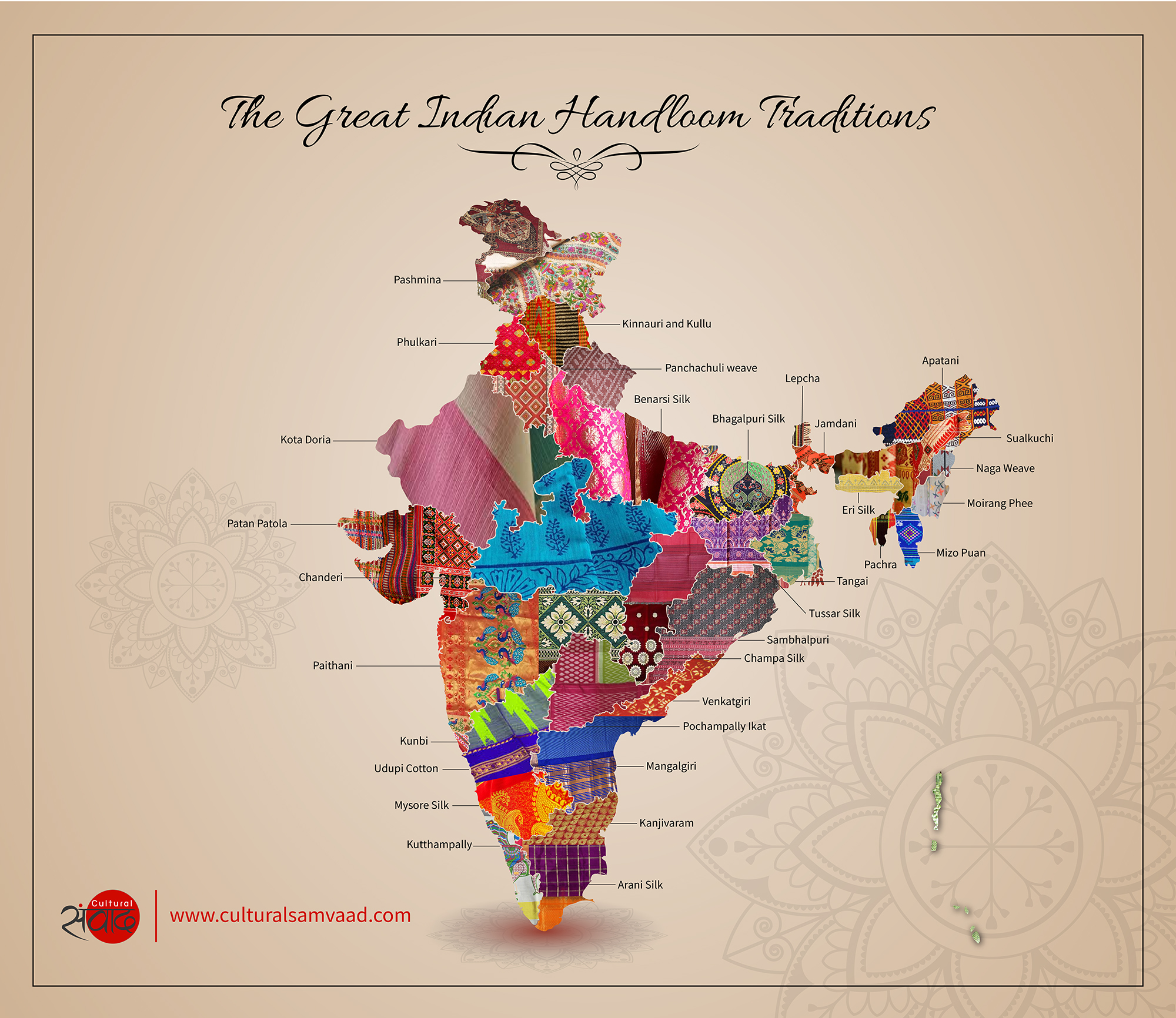

The Great Indian Handloom Traditions

From Kashmir to Kanyakumari and from the west coast to the east coast, the geography of India is replete with diverse local and regional handloom traditions. Team Cultural Samvaad attempted to put together just one more map mentioning some of the great Indian handloom traditions. Needless to say, we only managed to do justice to only a handful of them. Pashmina from Leh, Ladakh and Kashmir Valley, the Kullu and Kinnauri weaves of Himachal Pradesh, Phulkari from Punjab, Haryana and Delhi, Panchachuli weaves of Uttarakhand, Kota Doria from Rajasthan, Benarasi Silk of Uttar Pradesh, Bhagalpuri Silk from Bihar, Patan Patola of Gujarat, Chanderi of Madhya Pradesh, Paithani of Maharashtra, Champa Silk from Chattisgarh, Sambalpuri Ikat from Odisha, Tussar Silk from Jharkhand, Jamdani and Tangail of West Bengal , Mangalgiri and Venkatgiri from Andhra Pradesh, Pochampally Ikat from Telangana, Udupi Cotton of Karnataka, Kunvi weaves from Goa, Kuttampally of Kerala, Arani and Kanjeevaram Silk of Tamil Nadu, Lepcha from Sikkim, Sualkuchi from Assam, Apatani from Arunachal Pradesh, Naga weaves of Nagaland, Moirang Phee from Manipur, Pachhra of Tripura, Mizu Puan in Mizoram and Eri silk of Meghalaya are those that we managed fit into this version of the map. We are already working on the next version!

The Road Ahead for Indian Handloom Traditions

That piece of handwoven cloth is not only a link to our past but more importantly a link to the prosperity and well-being of 31 lakhs+ households across the length and breadth of India who are engaged in weaving and allied activities. The unorganised handloom sector provides direct and indirect employment to 35+ lakhs weavers (72% of these weavers and allied workers are women) from rural and semi-urban areas. (as per the Fourth Handloom Census of India)

Adopting handloom in clothes and furnishings is not just about preserving and reviving traditions but also about owning something that is handcrafted. Globally, luxury is increasingly about that which is not produced in factories but made by human hands and that which is organic. Handloom can also be luxury in the strictest sense of the term. NGOs, governmental organisations and couture designers are helping adapt Indian handlooms for the 21st century.

Notwithstanding large-scale attempts, our fervent belief is that the decline of Indian handlooms can be stemmed if and only if, the young Indians adopt her handlooms. No, we are not suggesting that they will wear only handlooms. We are hoping that they will bring back handlooms into their lives both as items of clothing and household furnishings.

So, are there bits of the great Indian handloom traditions in your life?

References

- Jayakar Pupul, Irwin John. Textiles and Ornaments of India (Museum of Modern Art publications in reprint). 1972.

- Position Paper on Indian Handloom Industry – FICCI Ladies Organisation (retrieved on 6th August 2019)

- https://www.craftscouncilofindia.org/indian-crafts-map/ (retrieved on 6th August 2019)

- https://www.craftsvilla.com/blog/indian-handlooms-from-different-states-of-india/ (retrieved on 6th August 2019)

- https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Kenoyer2004%20IndusTextilesfinal.pdf (retrieved on 6th August 2019)

Mysore Silk while a heritage textile is mot a handwoven tradition. The article while being eloquent, errs in the unsaid assumption that it is handloom.