Editor’s Note: This is the first part in a series of two introductory notes on Durga Saptashati. This piece narrates the stories given in this seminal text and the second piece places the text in the contemporary context.

Join our WhatsApp community

Introduction to Durga Saptashati

Durga Saptashati (दुर्गा सप्तशती) or the Devi Mahatmya (देवी माहात्म्य) is a centuries-old text recited by many Hindus especially during Navratri. It is among the loftiest of puranic compositions and is a part of the Markandeya Purana (one of the oldest 18 Maha Puranas in the Hindu tradition). The Durga Saptashati is also popularly referred to as the Chandi Patha (चण्डी पाठ) or simply as the Chandi.

The Saptashati (700 verses) has withstood the test of centuries[i] . At the time of its composition, it was probably an attempt to synthesise and crystallise millennia old traditions of goddess worship in India[ii]. It can be stated with conviction that it drew upon many well-known stories and myths in wide circulation at that time. The Saptashati is probably the oldest extant text in the world devoted entirely to a fiercely independent Goddess who is also The Supreme Being – The Ultimate Godhead – The Divine Feminine.

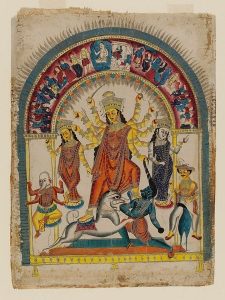

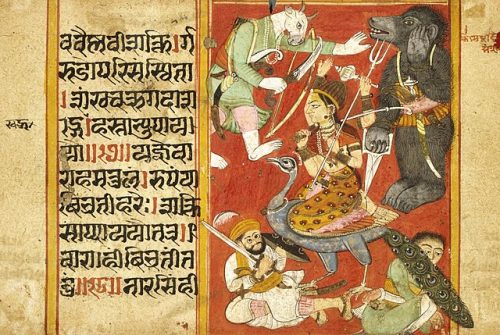

Image Courtesy: Rare Book Society of India

The Goddess Durga as we know her today in India and large parts of the world has been shaped to a large extent by this text. The biggest achievements of the Chandi are probably its contribution to the arts and iconography of the Goddess and its elucidation of the basic tenets of spiritual thought in a narrative form. The simple yet engaging narratives make abstruse philosophical ideas accessible and comprehensible to the common devotee. In addition, Durga Saptashati also serves as a basic text for re-evaluating and recasting gender equations in contemporary Indian and global social orders given that the composer(s) seem to have anticipated modern women empowerment issues millennia ago or maybe the times have changed but the debate hasn’t…

The Saptashati can be roughly divided into three main episodes (referred to as charitras ) over its thirteen chapters and a frame narrative to weave the three episodes together[iii]. It speaks of a king named Suratha and a merchant named Samadhi who meet while seeking refuge in the hermitage of Rishi (sage) Medha. A string of misfortunes had struck both of them and they had been deceived by their kin. Befuddled by their own circumstances and attachments to their lost possessions, they approached Rishi Medha for advice. The Rishi explained to them, that they, like the Universe, were controlled by the great Goddess Bhagwati Mahamaya[iv]. He proceeded to extol her major exploits in the text’s three episodes.

Episode 1 of the Durga Saptashati: Devi Mahamaya

The first episode (Chapter 1) narrates the myth of the demons (asuras) Madhu and Kaitabha who threatened Brahma. Brahma prayed to Goddess Yoganidra (deep sleep induced by Yoga), who was residing in Vishnu’s eyes, beseeching her to confuse the demons and awaken Vishnu to slay the demons. Propitiated by his prayers, Devi (goddess) Mahamaya (Yoganidra) did as requested. Vishnu woke up from his yogic slumber and killed the demons, thus saving the world and setting in motion the cycle of creation.

सर्वमङ्लमाङ्गल्ये शिवे सर्वार्थसाधिके ।

शरण्ये त्र्यम्बके गौरि नारायणि नमोऽस्तु ते ॥

Oh Narayani, salutation be to you. You are the auspicious in all auspiciousness and the one who blesses her devotees with all that is good. You are the one who accomplishes all goals, you are affectionate to those who seek refuge and you are the three eyed Gauri.

Episode 2 of the Durga Saptashati: Mahishasuramardini

The second episode (Chapters 2-4) of the text is devoted to the Devi’s most celebrated form – ‘Mahishasurmadini’. In ancient times, the devatas (gods in common parlance), led by Indra; fought against the demons, led by Mahisha (buffalo in Sanskrit – vehicle of Yama – commonly god of death). The gods were defeated by Mahisha and he usurped Indra’s powers to become Indra himself. Mahisha ruled over all realms of the Universe. The defeated gods then approached Vishnu and Shiva for help. The news angered them. Radiant energy (tejas) emanated from the faces of Vishnu, Siva, and Brahma, and from the bodies of Indra and other gods. This dazzling energy coalesced into a whole and expanded to fill the Universe. The incomparable brilliant energy transformed into a feminine form – the goddess Shakti.

Shakti laughed so loudly that the worlds trembled, and the oceans started churning on their own. Attracted by this loud sound, Mahisha’s demon army engaged with her in a battle which is described in vivid detail. She destroyed the demon army wreaking havoc with her weapons, the aid of her troops (ganas created by her) and her vahana (vehicle) – the majestic lion. Upon witnessing the defeat of his generals and army, Mahisha assumed the form of a buffalo and attacked the Goddess’ troops. A bitter and gory battle ensued. The battle climaxed in a duel between the agile Warrior Goddess and the fearless Mahisha. She leapt upon him, pressed him with her foot, and struck his throat with her spear. As the demon came halfway out of his own buffalo mouth, still fighting, the Goddess beheaded him, thus earning the laudatory title of Mahishasurmardini (she who killed Mahisha). The devatas, led by Indra, rejoiced and praised her with a hymn.

The motif of the Devi slaying the buffalo-demon Mahishasura continues to be one of the most pervasive of her iconographic representations. It should be mentioned that the motif predates the date generally given to the composition. Images of what can be construed as Mahishasuramardini can be traced to at least as long back as the 2nd Century BCE.

Episode 3 of the Durga Saptashati: Devi Ambika

The Saptashati then progresses to the third episode (Chapters 5-11) which recounts the ascent to power of the demon brothers Shumbha and Nishumbha. As usual, they displaced Indra and the other devatas from their heavenly positions and usurped their power. The Goddess had promised the gods that she would reappear/reincarnate whenever they were in trouble and save them. Remembering her boon, the devatas went to the Himalayas to appease Goddess Parvati and sang an exquisite hymn in her praise. Devi Ambika incarnated from the body of Devi Parvati in order to save the gods. Goddess Ambika’s unparalled beauty attracted the attention of Shumbha and Nishumbha, who wanted to control her. They demanded through a messenger that she should marry one of them. The Goddess explained that as per her vow, she would only marry someone capable of defeating her on the battlefield. Spurned by the ‘arrogant’ Goddess, the demons and their army engaged in a battle with her. After the defeat of their vast armies and ferocious generals like Dhumralochan, Chanda and Munda and Raktabeeja. Shumbha and Nishumbha eventually attacked the Goddess and were defeated and slayed by her thus re-establishing the reign of the devatas.

Within this episode, the Saptashati also weaves in the emergence of the Sapt Matrikas (mother goddesses) – Brahmani, Maheshwari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Narasimhi and Aindri. The matrikas are the shaktis (energies) of various gods (not consort goddesses). It also mentions the fierce Goddess Kali (black) who appeared from the face of Ambika which had turned black with anger.

Kali is also referred to as Chamunda, because she destroyed the demons Chanda and Munda, who served Shumbha and Nishumbha. She also annihilated the terrible demon Raktabija in this episode.

As is customary in texts of this nature, there is a chapter (Chapter 12) on the ‘phalashruti’ (fruits of listening and reciting) or Mahatmya of the Saptashati. The frame narrative culminates (Chapter 13) with Surath and Samadhi propitiating the Goddess with severe penance and beseeching her for boons of their choice – Surath in the material world and Samadhi in the eternal world.

The summary above is intended to serve only as an outline to its stories to enable further discussion. The Saptashati (originally composed in Sanskrit) has been translated into most Indian languages and English. A list of references is appended for further exploration.

देवि प्रपन्नार्तिहरे प्रसीद प्रसीद मातर्जगतोऽखिलस्य।

प्रसीद विश्वेश्वरि पाहि विश्वं त्वमीश्वरी देवि चराचरस्य॥

O Devi, you remove the sufferings of those who approach you and seek refuge in you. Please be gracious to us. O Mother of the Universe, please be benevolent. O Presiding Deity of this World, please protect one and all. O Devi, you are the ruler all that is moving and not moving in this cosmos.

Durga Saptashati 11.3 | दुर्गा सप्तशती ११.३

Do read Part II in this series to understand the contemporary context of this seminal text.

You may also like our note and video on ‘The Story of Mahisasurmardini’.

[i] The Markandeya Purana is variously dated by scholars to the 3rd century CE. The Saptashati (700 verses) is believed to be a later interpolation in the Markandeya Purana but is definitely dated before the 7th century CE. Please see: Upinder Singh. A history of ancient and early medieval India: from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Longman. 2008.

[ii] The tradition of Goddess Worship in in the Indus-Sarasvati Civilisation has been proven conclusively based on archaeological evidence. References to various forms of the Goddess are present in the Vedic Literature, Epics and other ancient Indian traditions.

[iii] The Saptashati frame is independent of the Markandeya Purana frame.

[iv] The word ‘Maya’ has many connotations – generally implies that which is unreal or illusory. The world is supposed to be Maya (unreal) in Vedanta and it is common parlance to say in Hindi – ‘sab moh maya hai’.

Select References:

- Allchin, Bridget (1997). Origins of a Civilization: The Prehistory and Early Archaeology of South Asia. New York: Viking.

- Danino, Michael (2010). The Lost River: On the Trail of the Sarasvati. New Delhi: Penguin India.

- Doniger, Wendy (2010), The Hindus: An Alternative History. New Delhi: Oxford University Press

- Lal, B. B. (2015). The RigVedic People. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

- Lal, B. B. (2002). The Sarasvati flows on. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

- Parpola, A. (2015). The roots of Hinduism: The early Aryans and the Indus civilization. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002), The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. New Delhi: Vistaar Publications.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education.

- Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press.

Add comment