Join Cultural Samvaad’s WhatsApp Community

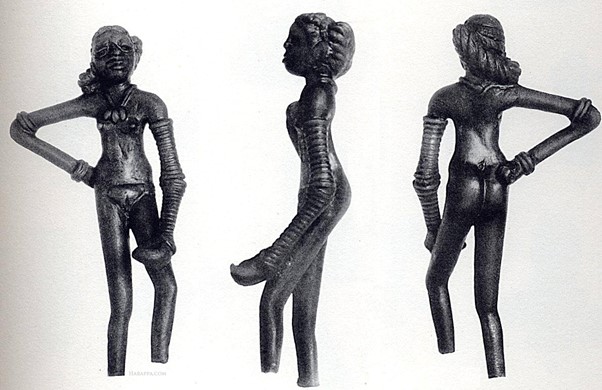

‘Awesome’… that is probably how innumerable young people, especially those who are native social media netizens, would describe our protagonist. She is none other than the one who has been dubbed the ‘Dancing Girl’ of Mohenjo-daro for almost a century now. And ‘awesome’ she is. However, make no mistake. She definitely does not seem to have ever been or is in awe of anyone or anything. She epitomises eternal fearlessness and that is just one of the infinite reasons that set her apart.

In the Words of the ‘Dancing Girl’ of Mohenjo-daro

My Rediscovery as the ‘Dancing Girl’ of Mohenjo-daro

It was the winters of 1926-27 in pre-independence Indian subcontinent. The Indus Valley civilisation had already been identified in 1921 at Harappa and then in 1922 at Mohenjo-daro, near the mighty Indus river in the Sindh region in Punjab and Sindh provinces respectively, in present-day Pakistan. The discovery of this ancient civilisation not only pushed back the history of civilisation in the subcontinent by over at least a millennium but also led to the rewriting of the history of the world and of human beings’ notions of their ancient past.

Shri Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni had been entrusted with the task of the aforementioned exploration season at Mohenjo-daro, one of the largest and important cities of the Harappan civilisation (Ernest Mackay was the principal excavator). The word Mohenjo-daro means ‘the mound of the dead’ and this mound of the dead was where I lay dead, well… almost dead… for thousands of years.

Know More: Important Sites of the Indus-Saraswati Civilisation

Like the Harappan civilisation, my exact age is unknown. I have no opinions to offer too… please pardon me… age is catching up. However, let me give you a hint. The civilisation is variously dated and the Mature Harappan Phase is generally assumed to be between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE. For the purposes of this discussion, let me peg my age at the approximate midpoint of the mature phase of my civilisation – ~2250 BCE with the caveat that I may have erred by a few centuries.

I was found in the HR Area at Mohenjo-daro in a Late-level house of Block 7 on January 26, 1927. The house where I probably lived for millennia before my rediscovery was a small structure, deep within the urban maze of the southwestern quarter of the city. I am merely 10.8 cms in height and cast in bronze using the lost wax method. Connoisseurs of art tell me that the currently extant Dhokra art in India not only continues to use the same or a similar lost wax casting method but also produces figurines that have unnaturally long legs and hands like I have.

In case you love details, let me reproduce for you an extract from Rai Bahadur Sahni’s exploration report to help you appreciate my seminal re-discovery better.

“No. LV. — This was originally a small dwelling and was found in such a dilapidated condition that it was not possible to make out its plan. Room 40 appears to have been a bath and has a well-preserved paving consisting of a single course of burnt bricks laid flat upon a substratum of alternating rows of burnt and sun-dried bricks. Such construction has not been noticed in any other building on the site. The chief interest of this building lies in a number of valuable antiquities yielded by it, the most remarkable among them being a bronze statuette of a naked dancing girl (Hr. 572). It is in perfect preservation except for the feet, which are broken off. The existing height is 4 ” and the figure is characterized by coarse negroid features but not devoid of a peculiar primitive vigour. The hair is gathered in a large mass near the right ear, the left leg bent forward and the right hand placed on the right hip. The left arm, which hangs down, is covered with bangles from the shoulder to the wrist and explains why so large a number of ornaments of this class in copper, conch, faience and terracotta have been found both at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa.”

My Current Abode – National Museum, New Delhi, India

Today I have a special place of pride at the National Museum in New Delhi, the historic capital of my land – India. I am one of those lucky ‘artefacts’ (that is how I am referred to) that were not carried away to adorn overseas museums and continue to live among my descendants.

In case you have not seen me, I am reproducing an extract of a modern description by an erudite scholar of my civilisation.

By Saqib Qayyum – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

“The figure is a very thin young woman, standing upright, with her head tilted slightly back, her left leg bent at the knee. There is little sense of flesh on the body or anatomy to the joints, which is a stylistic feature shared with some later Indian sculpture. Her right arm is bent, with her hand placed provocatively on the back of the hip, the thumb outside a clenched fist. The left arm rests slightly bent on the thigh of her left leg. The thumb and forefinger of this hand form a circle, and it is apparent that she once held a small object, possibly a baton of some kind. She is naked, except for some adornments. Around her neck is a small necklace with three large pendant beads. On her left arm she wears twenty-four or twenty-five bangles, which would have severely restricted the mobility of the elbow in a living person. The right arm has four bangles, two at the wrist and two above the elbow. Her hair is coifed into a kind of loose bun, held in place along the back of her head much the same as some Indian women wear their hair today. The artist has rendered this feature in detail.” (Possehl, 2002)

Let me also quote Sir Mortimer Wheeler who paid rich tributes to me while describing me in the following terms; ‘There is her little Baluchi-style face with pouting lips and insolent look in the eye. She’s about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl perfectly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There’s nothing like her, I think, in ancient art.’

‘As in some of the stone statues, the eyes are half-closed, and the expression on the face suggests disdain. A necklace, whether of beads or a thick cord, has three pendants or amulets suspended from it. Though the proportions of this figure are not correct, the arms and legs being much too long for the body, it is nevertheless an exceptionally fine piece of work for such an early period. The abandon expressed in face and limbs is quite realistic.’

Who Am I? Who is the Dancing Girl?

Am I a dancer? Well, that is certainly open to question.

Notwithstanding the controversies around who I was and who I am, I can definitely aver that some of my characteristics are still characteristic of women in parts of the country. My hairstyle is still a rage. It is probably something that comes naturally to most women especially in the subcontinent to keep their unruly hair in its place. Bangles similar to the ones that cover my left arm still adorn the hands of women in Gujarat and Rajasthan and elsewhere. My necklace along with my pendant beads would be considered stylish even in the 21st century.

Since we just alluded to bangles let me add that ‘bangles were a common item of Harappan dress. Finds from burials confirm this: Women usually wore a number of bangles,either on both arms or on just the left, narrow ones around the wrist, and wider ones above the elbow.’ (McIntosh,2008)

Why was I identified as a dancing girl or nautch girl in the first place? Let me quote to help you understand.

‘Almost, indeed, it is a caricature, but, like a good caricature, it gives a vivid impression of the young aboriginal nautch girl, her hand on hip in half-impudent posture, and legs slightly forward, as she beats time to the music with her feet. Small, too, as this figurine is, the modelling of the back, hips, and buttocks is quite effective, and in spite of obvious defects shows sound observation on the part of the artist.’ (Mackay)

‘…For here we clearly have a dancer or nautch girl of aboriginal stock represented, and we may reasonably infer that girls of this class were accustomed to wear nothing more -than their ornaments when dancing, though it would be rash to suppose that they ordinarily went naked.’ (Marshall, 1931)

Apart from some inherent prejudices and/or biases in the statements above, my pose to many seems to convey that I am a dancer and can probably be linked to some ‘charis’ used in classical Indian dance. And young dancers from the subcontinent look up to me for inspiration and I am proud of it. Professor V. S. Agrawala surmised that my poses had been discussed in the Rig Veda. ‘The bronze dancing girl is a matter-of-fact example in which the rather longish legs and arms and the slightly tilted head bespeak the rhythm of her movements. The right arm, flexed at the elbow, is placed on the hip and the left, profusely loaded with bangles; (खादयः – RV.I.166.9, VII. 56.13 and खादिहस्त – V. 58.2) is suspended and touches the left thigh (लताहस्त). She appears to be the model of Nṛitū (नृतू), a female dancer with whom Usha (the Goddess of Dawn) is compared to in the Rigveda, wearing on embroidered garment and opening her breasts (अधि पेशांसि वपते नृतूरिवापोर्णुते वक्षं, RV. I.92.4).’ (Agrawala, 1965)

Incidentally, my facial features like my broad nose and large lips have been used to indicate racial affiliations – Dravidian; Nubian; Baluchi and Proto-Australoid. Piggott even suggested, ‘When we are describing the Harappa culture we shall, I think, recognize a Kulli girl in a foreign city.’ (after Possehl, 2002)

When I made my way to the famous exhibition title ‘India And The World: A History In Nine Stories’, contemporary art historian and curator, Naman Ahuja posited that perhaps my identification as a dancing girl was coloured by the gender bias of the archaeologists who discovered me in the 1920s. ‘Women were regarded either as objects for titillation or venerated as the mother goddess. And in between the two, there was no other role for them as equals or any other way.’ He noted that I am wearing has bangles all the way up to my left arm but my right arm is bare, as any working person would like to have. His hypothesis is that my decorated left arm and a bare right arm implies that it was left free for labour or for war? ‘If she was a dancing girl by profession, surely it would have been relevant to keep both arms decorated? Look at the way she is standing. Look at her confidence. One arm on hip. Head thrown back. The way her hand is sculpted, there might have been a spear in her hand. Is she a warrior figure? Could she be a soldier rather than a dancing girl?’

Recently Thakur Prasad Verma, a retired professor of Banaras Hindu University, has claimed that I am Goddess Parvati in a research paper published in Itihaas, the Hindi journal of the Indian Council of Historical Research. The research paper, titled ‘Vedic Sabhyata Ka Puratatva (Archaeology of Vedic Civilisation)’, links me to Shiva as a Hindu goddess and is the first such claim.[ii]

A Second Bronze Dancing Girl (DK-12728) was also found by Mackay in his final full season at Mohenjo-daro in 1930-1931. This statuette is not as well preserved as me and has not added any new clues to help in understanding me. Mackay observed; ‘Despite the damage by corrosion it is clear that the workmanship and finish of this later figure is inferior to that found earlier.’

And the mystery and the argument continue. ‘If she was a dancer, it would foreshadow later Indian sculpture, which is much influenced by this theme. … On detailed examination of the bronze dancing girl from HR Area one sees a subtlety to the expression and pose that defies description and cannot be captured by the camera…We may not be certain that she was a dancer, but she was good at what she did and she knew it.’ (Possehl, 2002)

Let me conclude this discussion with two questions.

Who do you think I am? Do I matter to you?

My brief response to the ‘Dancing Girl’ of Mohenjo-daro

This is my response to the questions that our protagonist poses. When I first encountered our stunning, enigmatic protagonist as a young Indian girl, she hardly reminded me of a dancing girl. The term ‘dancing girl’ incidentally sounds akin to colonial stereotyping at its worst in the original identification though Professor Agrawala’s hypothesis needs more detailing. Irrespective of her profession or vocation, she had and has the airs of an independent, nonchalant, proud, powerful, fearless young girl who is ready to take on the world. She is not a prisoner to any definition. She could have been a warrior, a poetess, a goddess, a dancer, a fashionista or anything else that one would like her to be or she would have liked to be. She is a living symbol of she who can survive the onslaught and ravages of time and emerge victorious. She was left (without company?) to the elements for thousands of years and lived through it all and yet stands tall.

The Original Fearless Girl

Years later in 2017, I read about the 50 inches tall (~127 cms), bronze ‘Fearless Girl’ which was originally installed in front of the New York Stock Exchange Building in Manhattan in New York City. She was strategically located in a manner that she would face the iconic ‘Charging Bull’ and the plaque below her stated; ‘Know the power of women in leadership. SHE makes a difference.’.

In the 21st century, her sculptor clarified for the benefit of onlookers – “I made sure to keep her features soft; she’s not defiant, she’s brave, proud, and strong, not belligerent“. She further averred that the sculpture was modelled on two children from Delaware “so everyone could relate to the Fearless Girl.” (Italics mine. Added for emphasis.)

The statue has since then been moved to another location. From threatening the bull to destroying the work of art that the bull is, many reasons have been advanced for the ‘Fearless Girl’s’ removal but that is a story for another day.

So, what is the connection? I have always thought of the so-called ‘Dancing Girl’ of Mohenjo-daro as the embodiment of fearlessness and defiance – she is probably the ‘original fearless girl’, if one ever existed or maybe she is every ‘fearless girl’ who has existed, does exist and will exist till the end of time.

The Original Fearless Ordinary Indian

To extend the metaphor further, she is not just the original fearless girl but also every ordinary nameless yet fearless Indian who has survived multiple trysts with destiny and managed to keep herself/himself afloat. She is the ordinary Indian citizen who may not always be credited with creating history but is the one who keeps Indian history going. It seems to be a strange coincidence of fate that she was re-discovered on January 26, 1927. No one can over emphasise the importance of January 26 in modern India and in the life of every Indian.

This diminutive statuette has no clarifications and/or qualifications attached to her and has the semblance of a powerful human being in her own individual right. This nameless young woman does make a difference. So much of a difference, that today many narratives of the subcontinent’s history begin with her. And that even today, many people across the Indian border believe she should be living in Pakistan and not India.

The Dancing Girl housed at the National Museum, New Delhi is not just an exquisite piece of art, antiquity and heritage. She is of course all that but she is much more than being a prized treasure of yore. It is time for India and Indians to recognise her and recognise her unbridled fearlessness and project her as an enduring emblem of the might of the fearlessness of an ordinary human being and the indomitable position of feminine power in the history and culture of the subcontinent. It is time to recognise her as an enduring link to our past. It is probably also time to change her narrative for the 21st century and for centuries to come.

Editor’s Note: This piece is structured as a first-person account from our protagonist. The opinions and feelings are expressed by her are fictional in nature but her facts are impeccable. She remains true to those facts that are known and/or those that are generally accepted and/or in the public domain. Her account is interspersed with my personal notes and observations.

Select References

- Agrawala, V.S. 1965. Studies in Indian Art. Varanasi: Vishvavidyalaya Prakashan.

- Craddock PT. 2015. The metal casting traditions of South Asia: Continuity and innovation. Indian Journal of History of Science50(1):55-82.

- MacIntosh, Jane R. 2008. The Ancient Indus Valley : New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- Marshall, John.1931. Mohenjo daro and Indus Civilization. Arthur Probsthain.

- Possehl GL. 2002. The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Walnut Creek, California: Altamira Press.

- Singh, Upinder. 2008. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India.

The elite statue is of a warrior queen who is standing in a VICTORY POSE AND HOLDING a spear or victory rod in her hand (notice a large hole made by folded fingers of the hand)

The jewellary and styled hair (thousands of years ago) are an exceptional elegant way to present.

One can even see the QUEEN of CHANDER GUPT MAURYA (333 BCE times) in very same pose of resting her left hand over left hip (see Magadh coins showing Chander-Gupt with Greek as well as Indian wives

The same pose and bangles in the upper arms can be seen in the carvings ( 200 BCE times) showing Queens and King ASHOKA THE GREAT.

See DGHC

DR GUPTA HARAPPAN CODE 202